Histoire

Un siècle de vélo artisanal français, au coeur des arts et de l’élégance parisienne.

“Fabriquer des vélos comme on fait des sculptures, emblèmes de liberté”

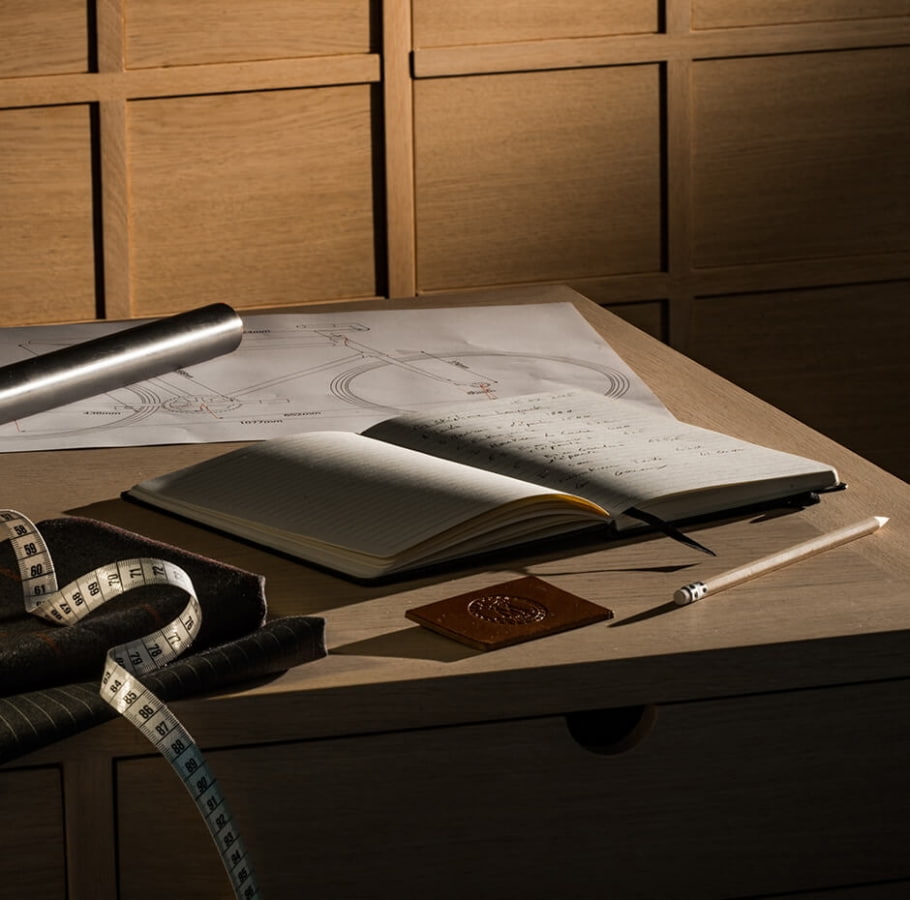

Savoir-faire

Aujourd’hui comme en 1912, nos collections célèbrent la passion et le savoir-faire des artisans français, et une certaine idée du vélo de luxe, au service de la mobilité urbaine et de l’élégance parisienne.

“Chez Maison TAMBOITE Paris, nos produits sont avant tout des créations”

Sur-mesure

Comme un costume, ou un soulier, le vélo est une extension du corps de son propriétaire. Il doit en épouser la morphologie, sans la contraindre.

“Un vélo parfaitement adapté à une morphologie et un type de pratique”

Technologie

La quête de perfection que nous mettons en œuvre dans la réalisation artisanale de nos produits guide aussi nos choix en matière de matériaux, de composants, et de technologie embarquée.

Univers confidentiel

Découvrir la Maison Tamboite Paris, c’est aussi accéder à nos collections et à toute la richesse d’un univers éminemment parisien, exclusif et volontairement confidentiel.